Past, Present, and Future on Little River

Lowry Pei on history of Little River

added to website January 25, 2011

(source: http://lowrypei.wordpress.com/products/past-present-and-future-on-the-little-river/)

[published in a slightly different form in Belmont Citizens Forum newsletter, summer 2008]

In the nineteenth century, the area west of Fresh Pond, extending to Little Pond in Belmont and Spy Pond in Arlington, was still known as the "Fresh Pond Marshes." Around 1860, according to Birds of the Cambridge Region by William Brewster, "the meadow grass which covered them was regularly cut and drawn off in hay wagons." The water in the marsh's streams was clear and drinkable. It was possible to canoe from Fresh Pond up the Little River, through the marshes, to Little Pond and Spy Pond without once getting out of one's canoe.

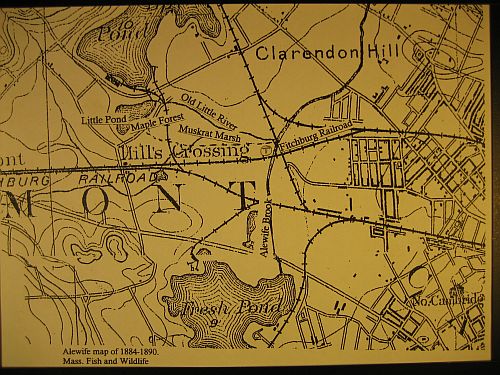

I've been exploring the Little River pretty regularly since last September – if "exploring" is the word for visiting a place so many people have set foot in before. There is a newness that waits to be found every day, and not many people go into the Alewife Reservation, compared to the number who whiz by it on Rt. 2 or Fresh Pond Parkway. The Little River as we know it today flows out of Little Pond near Hill Estates; soon thereafter, Wellington Brook enters it at a wide place in the stream known as Perch Pond. The Little River continues on an almost straight course to the Alewife T stop, where it flows under Rt. 2 and its name changes to Alewife Brook.

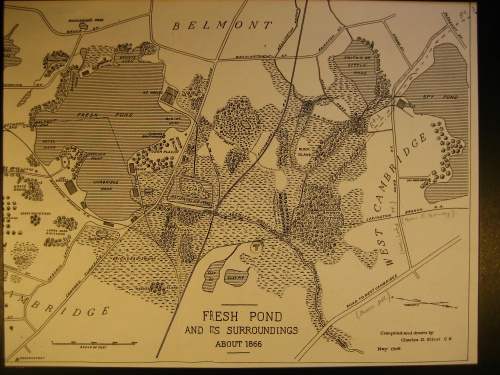

It's fascinating to compare the area as we know it today to a map of Fresh Pond and its surroundings, circa 1866, that was drawn in 1906 by Charles D. Elliot.(Click on the image to view full size; you can then zoom in.)

The present-day Alewife T stop (indicated by a circled T in pencil) is in a spot that, in 1866, had marsh on 3 sides, with two clay pits to the southeast (the local brick industry was in full swing) and beyond them a "Wooded Island" (about where Cambridge's Danehy Park is today). To the south of the T stop was a "Maple Swamp" (currently Fresh Pond shopping center), to the southwest and west "Glacialis or artificial ice pond" and "Pine Swamp" (mostly offices, warehouses, stores, light manufacturing). To the northwest of the T stop was all marsh, with the Little River running through it. Today that area is office parks, industrial and high-tech firms, and the Alewife Reservation. The Route 2 of today (dotted pencil line) crosses what was a "Cart path shaded by willows" and the "Site of former Heronry of Night Herons, also of Robin Roost."

People have been engineering this watershed for many years, by digging ditches to drain fields, re-channeling streams, damming Alewife Brook, and so on, for different reasons at different times.

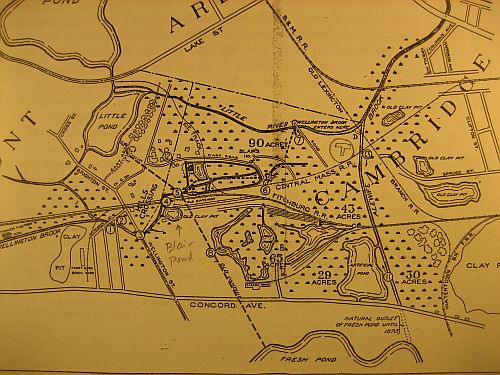

Above is a detail of a 1901 map, with the T stop indicated in pencil. If you zoom in on the full-size image just above the "Ave." in "Concord Ave." (street near bottom of map), you'll see a "packing house," which is the slaughterhouse mentioned below.

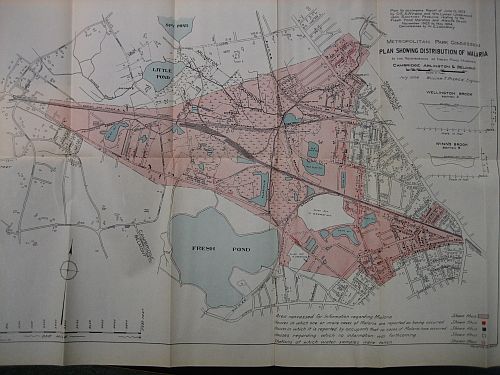

As population and industrialization grew in the late 19th century, the marshes, and the water supply of Cambridge and part of Belmont, were subject to multiple types of pollution. The worst offender was a slaughterhouse, built north of Fresh Pond in 1878, that dumped its waste into the wetlands. Cambridge and Belmont traded accusations about whose sewage was polluting the area. Malaria was rampant around the marshes. By 1900 local conditions had become a recognized crisis. The Cambridge Chronicle of August 4, 1900, ran an article headlined "Wellington Brook Must Be Purified," sub-headed "Petitioners Declare That Its Condition Is Offensive and a Menace to Public Health – Thursday's Hearing at City Hall."

This 1904 map shows houses, marked with red dots, where malaria cases occurred (can be seen if you zoom in on full-size image).

Today's Little River is in fact a new channel that was dug in response to the public health crisis and the need to drain the marshes better.This map shows both the old Little River (so labeled) and the new channel (a dotted line connecting Little Pond and Alewife Brook, running just above the words "Hill's Crossing").

We owe it, and indirectly the whole Alewife Reservation, to a project authorized in 1903 "for improving the sanitary and drainage conditions of Alewife Brook" and the marshes, "under the joint action of Arlington, Belmont, Cambridge and Somerville." Once again, it was necessary to re-engineer the watershed, to fix problems humans had brought on themselves. By 1908 the state had taken the land that is now the Reservation, taking the advice of John R. Freeman, civil engineer, that "The cleanliness and care of the banks of this drainage channel ought to be protected by public ownership of a strip of land on both its sides." Originally all of that land was known as Alewife Brook Parkway.

In March of 2008 I decided to see what I could find of the original Little River, which ran to the north of the current channel and entered Alewife Brook at a slightly different point (Alewife Brook then flowed out of Fresh Pond). Interestingly, a remnant of the old Little River is shown on at least one map that shows buildings constructed in the 1970's or later, even though by then the new channel had existed for 60 years. Behind a motel by the side of Route 2, formerly the Susse Chalet, I saw this through the back fence:

To the left is a newly built office building called Discovery Park, and its parking lot.

This looked more than promising. Next to the motel is the ruin of the nightclub known as Faces (its decrepit sign is still there), deserted for years now. Nature is visibly reclaiming its parking lot; moss is growing on it, and grass is coming up through big cracks in the asphalt. It won't be too long before this space is overgrown. The building is a wreck and behind it is a wetland; despite roadways and parking lots, these are still the Fresh Pond Marshes. According to Elliot's map and many others, this is also where the Little River used to flow. From what was once the riverside, there is a picturesque view of the ruins.

the ruins of Faces

Along Acorn Park Drive, there's more left of the Fresh Pond Marshes than one might imagine while driving by in a car on Route 2.

There is a definite current of water flowing out of the ultra-manicured bit of stream beside Discovery Park, under the roadway, and emerging on the other side.

From this point, the water flows west alongside Acorn Park Drive and into a marsh that drains into the present-day Little River. The living continuity, from the wetland behind Faces to the present-day river, matters to me; it feels as though the landscape preserves a faint memory of the Little River that once was. The past is not quite as distant as it might seem.

It never hurts to know a little more history. In the past 150 years, there have been losses and gains on the Fresh Pond Marshes, some of which are obvious, and some of which are not. Looking at the map of the area circa 1866, one can't help but regret the loss of a "cart path shaded by willows"; but at the same time, slaughterhouses no longer dump their waste products into the local water supply. A proposed subdivision that was on a 1903 map next to Perch Pond (street names and all) was never built; the Metropolitan Park Commission prevented that by taking the land. The fact that malaria was once a threat here is not obvious to us today.

My wanderings up and down the Little River tell me that today the Fresh Pond Marshes area is mostly ignored. Some homeless people live there, some people who live nearby go there to enjoy it, most people rush by. But it's still there, and though it's certainly not nature primeval, it is nature. Its history says that it is both open to being shaped by human interventions, and persistently itself. The original channel of the Little River is still a wetland for a reason. We can't change the fact that water goes where it needs to go. We're steadily moving away from the worst excesses of 19th-century industry, and simultaneously creating excesses of our own, like our dependence on cars and our level of consumption. Our standards of public health are infinitely superior to those of a century ago, and still evolving. I hope that our notion of public health, our notion of our own self-interest, will once again come to include the health of the Little River and the local marshes, Wellington Brook, Blair Pond, Perch Pond and all the rest of the ponds and waterways named and unnamed. I don't think this is a sentimental idea. It certainly was not in 1900, when the public demanded action before the Board of Health.

People get used to everything, and the human time horizon is very close in. We tend to think that the way things are today "just is." But the way things are today is a history of decisions, some good and some rotten, the outcome of a chronicle of consequences intended and unintended. There's no way we're going to "just leave nature alone" around here; it's centuries too late for that. The arrow of time only points one way, and we have one choice: let go of the past. But letting go of it does not mean forgetting it.

Soon enough, we will be someone else's past. We'll leave behind our own legacy of decisions. Let's hope they are as good as some that were made a century ago.

Wetland, Fresh Pond Marshes, May 13, 2008.

|