SOMERVILLE — Pity the Mystic.

The

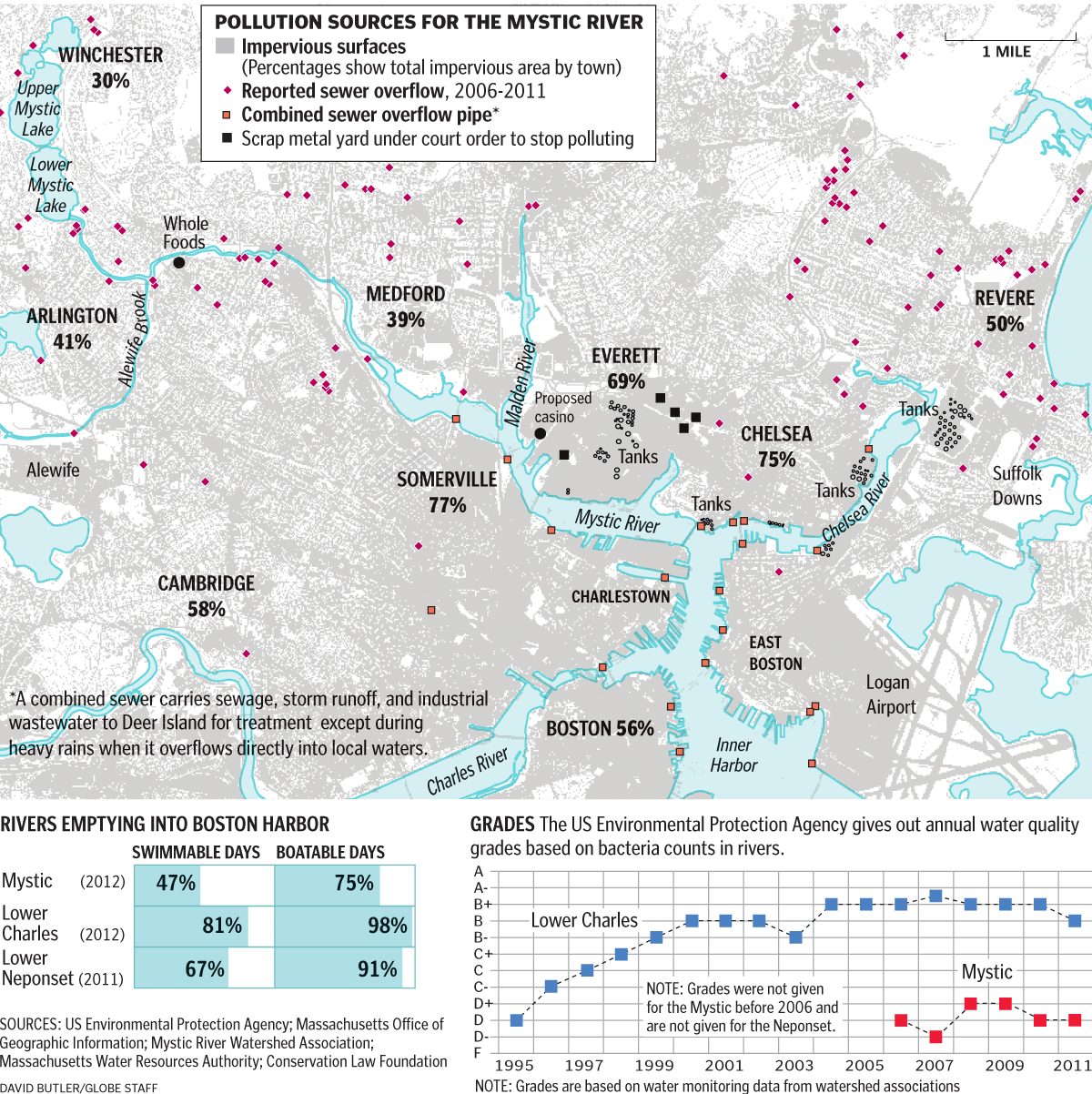

gritty 7-mile river that flows from Medford and Arlington to Boston

Harbor rarely earns better than a "D" on the federal government's annual

water quality report card. Raw sewage still spews into the river during

severe storms — including almost 4 million gallons in December. Vast

mats of invasive water chestnut clog the surface in places.

Almost

30 years after Boston's sewage-laden shores began their transformation

into sparkling, swimmable beaches, the Mystic — one of the three main

rivers that flow into the harbor — lags far behind the beloved Charles

or scenic Neponset in water quality and public access. Hidden in spots

and surrounded by asphalt, it serves as a stark symbol of the cleanup

challenges remaining for waterways in cities nationwide.

"When

you go downstream, really, it's an urban ditch,'' said Neil Clark, who

lives on one of the two Mystic Lakes that drain into the river and knows

the area well. "It is just down-beaten."

The

Mystic — the namesake of the celebrated Dennis Lehane crime novel — has

long suffered in the shadow of the longer and more visible Charles and

Neponset rivers. It is a far cry from the idyllic waterway portrayed in

the popular Thanksgiving poem "Over the River and Through the Woods,"

with densely settled suburban towns such as Medford in its northern

reaches and scrap metal plants and tank farms downstream in Everett and

Chelsea. 'People perceive this river as ruined, but it is a living

system that is struggling to thrive.'

But it is starting to

attract attention, as more development is proposed near the river,

including casino magnate Steve Wynn's bid to build a casino and resort

on the site of a former Monsanto Chemical plant in Everett. A herring

run was robust last year, and the Environmental Protection Agency has

stepped up enforcement to prevent illegal discharges of pollutants into

the Mystic, including fining Suffolk Downs $1.25 million last year for

dumping horse manure and urine into a nearby wetland.

Court-ordered

work to separate sewer pipes from storm drains is underway in Cambridge

and Somerville, including a $116 million project for Alewife Brook,

which flows into the Mystic. And the environmental advocacy group

Conservation Law Foundation, hoping to accelerate the pace of the Mystic

cleanup, began suing scrap metal plants near the river last year,saying

they did not have proper permits to discharge industrial pollutants.

Yet

ever since the EPA began grading the Mystic seven years ago, there has

been no lasting improvement in water quality, largely because the river

faces so many of the persistent problems of urban rivers: Sewer and

storm pipes overflow, and pet waste, industrial pollutants, and lawn

fertilizer drain from acres of surrounding paved surfaces. While the

Charles and Neponset have some of the same challenges, the Mystic's are

more extensive, many water specialists agree.

"You name the

problem, we have it,'' said EkOngKar Singh Khalsa, executive director of

the Mystic River Watershed Association. "Part of the problem is that we

were settled first, we are so old. People perceive this river as

ruined, but it is a living system that is struggling to thrive."

Khalsa

and other advocates say severe cuts to the state Department of

Environmental Protection's budget have stymied progress, as has the

agency's reluctance to fine communities for not stopping pollution such

as leaking sewage.

Kenneth Kimmell, DEP commissioner, said the

agency has worked hard, despite deep budget constraints, to take

aggressive action to clean up the river. Cuts forced his agency to halt a

two-year effort in 2009 to track pollution in the river to its source,

but that may soon change if the Legislature approves money for the

testing.

"A clean and healthy Mystic River is a high priority,"

said Kimmell. "The governor's proposed budget would enable us to

reinstate that program and get the river cleaned up more quickly and

more thoroughly."

Advocates for the river also decry periodic

large dumps of raw sewage. During a stormy Dec. 27, Massachusetts Water

Resources Authority workers released a mix of untreated sewage and

rainwater into the river across from the Medford Whole Foods Market to

relieve pressure on the system. In all, almost 4 million gallons of the

sludge flowed into the river from various discharge pipes.

River

advocates are concerned that the volume of releases into the Mystic

might far exceed those into the Charles and Neponset, but they say they

do not know for sure because reporting has not always been accurate.

"Although these releases are well-known and well-understood, they are in fact violations of the Clean Water Act,'' said Khalsa.

Massachusetts

Water Resources Authority officials say they are working hard to stop

such releases, but they come only about once a year and tend to flush

out of the system quickly. And if they did not occur, they add, the

entire system would back up during heavy storms. They say their data —

based on water quality readings from the middle of the Mystic, as

opposed to testing near tributaries as the watershed association does —

show the river's water quality is on par with the Charles.

"We

view these [releases] as something of a last resort, but the lesser of

two evils,'' said Fred Laskey, the water agency's executive director.

Those

large releases are only a piece of the problem. A bigger one may be

pavement: It is difficult to prevent waste from washing into a river

from every street, parking lot, and sidewalk. The Mystic flows through

communities with an enormous amount of pavement — 77 percent of

Somerville's land area is paved over, for example — that prevents

rainwater from seeping into the ground to be cleansed.

"In many

ways, these are the next-generation environmental challenges,'' said

Bruce Berman of Save the Harbor/Save the Bay, a Boston-based advocacy

group. Fixing those problems requires a reengineering of cities to keep

water local, such as using barrels to catch rainwater flowing off roofs

to water plants, or developing porous pavement to let rain seep into the

earth.

Yet Berman and other river advocates say there is an

easier way to help the Mystic: Make it more visible, as a way to build

public, and then political, support to clean it.

Unlike the

Charles that flows through the heart of Boston and the Neponset, which

is garnering attention in part from a new bike trail along its most

densely populated areas, the Mystic is largely hidden behind fences,

industrial sites, and old buildings.

Many of the communities

along its filthiest parts are poor. The watershed association holds

yearly kayak and canoe races and cleanups, but making the Mystic more

accessible remains a challenge.

There is no better time to get

the public involved, advocates say, because the Mystic may be in for

worse news. The EPA announced last month that it is working on new

language to give financially struggling communities more time to comply

with Clean Water Act regulations. Requests to the EPA for comment went

unanswered.

"The real message there . . . is we are going to

make it easier for you to pollute,'' said Christopher Kilian, director

of the Conservation Law Foundation's Clean Water Program. "We made a

decision as a society that these public resources were going to be

treated the same . . . all waters were going to be protected equally. I

worry about the Mystic."

Beth Daley can be reached at bdaley@globe.com. Follow her @Globebethdaley.

SOMERVILLE — Pity the Mystic.

SOMERVILLE — Pity the Mystic.